The Disruption of Higher Education and the Fourth Industrial Revolution

Higher education is at the crossroads of economic, demographic, technological and global change. The U.S. higher education system has long embraced a degree-based model that was designed to improve the nation’s manufacturing, agricultural and transportation infrastructure. The Morrill Land-Grant Acts of 1862,[1] while creating the land-grant colleges, also established the 17 historically black colleges and 30 American Indian colleges. Land-grant institutions also were among the first to admit women to higher education. While these groundbreaking acts have served our nation well and were foundational as the world moved through the internet and mobile economies, the dependence on them is likely to be less, as much of the world moves to what has been coined the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) by Klaus Schwab, the executive chairman of the World Economic Forum.[2]

This Fourth Industrial Revolution is expected to be disruptive to many industries as automation, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, predictive analytics and the increased digitization of our world will reshape the needs of the workforce. Higher education institutions that were slow to adapt to the mobile and internet economies (the Third Industrial Revolution) are finding themselves unable to adapt to the beginning of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, with many closing their doors or merging with other colleges and universities. Therefore, higher education has learned that they are no longer at the center of economies and must adapt more quickly as the shift to 4IR accelerates. The timeline has only accelerated as a result of the pandemic.

Degrees, Other Credentials and New Jobs of the Future

With the evolution to the 4IR accelerated due to the pandemic, many new jobs are expected to be created, while others will be eliminated. In addition, it is estimated that 75 million[3] workers in the United States will need to be reskilled while worldwide, upwards of one billion will need new skills by 2030.[4] As a result, higher education can no longer rely solely on a credit-based model, often taking four or more years and 120 credits to complete an undergraduate degree and another two years and 30 credits for a graduate degree. More modular and flexible education that better responds to the market and its occupational masses will be needed. While reskilling will cut across many demographics, those in lower income brackets are most at risk.[5] In addition, many degrees earned five to twenty years ago have or will become obsolete in the new economy.

According to the World Economic Forum, the highest levels of growth could span seven clusters:[6]

- Data and AI, where annual growth will be 41% globally, creating 450,000 job openings. These could include AI Specialists, Data Scientists, Data Engineers, and Big Data Developers among many others.

- Engineering and Cloud Computing, which could experience 34% annual growth, creating approximately 450,000 job openings globally. These could include Site Reliability Engineers (Cloud Computing), Python Developers (Engineering), Full Stack Engineers (Engineering), and JavaScript Developers (Engineering) among many others.

- People and Culture, which could experience 14% annual growth, creating approximately 400,000 job openings globally. These could include Information Technology Recruiters, Human Resources Partners, Talent Acquisition Specialists, and Business Partners among many others.

- Product Development, where annual growth will be 23% globally, creating 250,000 job openings. These could include Product Owners, Quality Insurance Teachers, Agile Coaches, and Software Quality Assurance Engineers among many others.

- Sales, Marketing and Content, which could experience 28% annual growth, creating approximately 690,000 job openings globally. These could include Social Media Assistants (Content Production), Growth Hackers (Marketing), Customer Success Specialists (Sales), and Social Media Coordinators (Content Production) among many others.

- Care Economy, which could experience 21% annual growth, creating approximately 160,000 job openings globally. These could include Medical Transcriptionists, Physical Therapist Aides, Radiation Therapists, and Athletic Trainers among many others. As a result of the pandemic, employment around healthcare administration may also increase.

- Green Economy, which could experience 36% annual growth, creating approximately 117,200 job openings globally. These could include Methane/Landfill Gas Generation System Technicians, Wind Turbine Service Technicians, Green Marketers, and Biofuels Processing Technicians among many others. The pandemic, as well as fires on the West Coast of the U.S., have created migration shifts that will impact how are cities will be operated and designed in the future. Occupations related to micro-mobility and new forms of transportation will be more evident in the new economy.

Job Growth and Contraction is Expected in the New Economy

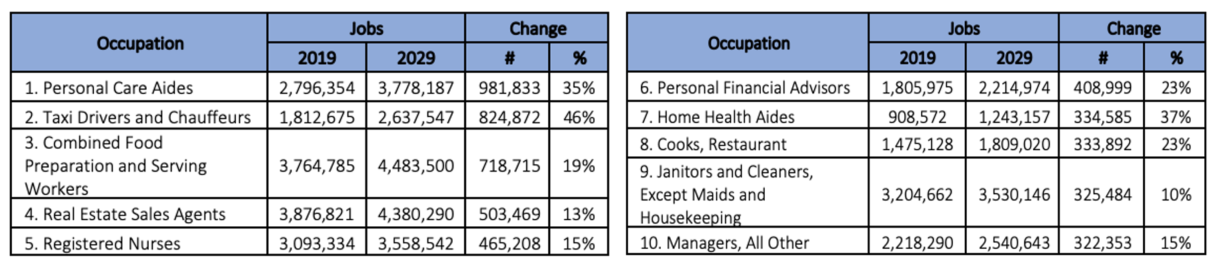

While the data above predicts an economy with many new jobs, changing demographics, an evolving economy and some anomalies that may or may not occur in a Fourth Industrial Revolution will affect growth. The two tables below from Economic Modeling Specialists International (Emsi) and its 2020.1 dataset reveals a number of high growth jobs and those in decline. Table 1 lists the top ten growing occupations from 2019 to 2029 in the U.S. The highest increase in number of jobs is personal care aides with 981,833 new jobs, this in addition to 465,208 registered nurses and 334,585 home health aides. The increase in demand for these jobs ties into an aging population as Boomers get older and retire. The increase in the taxi driver and chauffeur category is likely a result of ridesharing; however, this could be negatively impacted as automobiles become self-driving, most likely in 2030 and beyond. While forecasts below suggest growth in jobs related to the food service and restaurant industries, some reports suggest that food delivery and a push toward healthier and plant-based proteins could reshape these categories.

Table 1: Top Growing Occupations (based on volume) in the U.S. (2019-2029)[7]

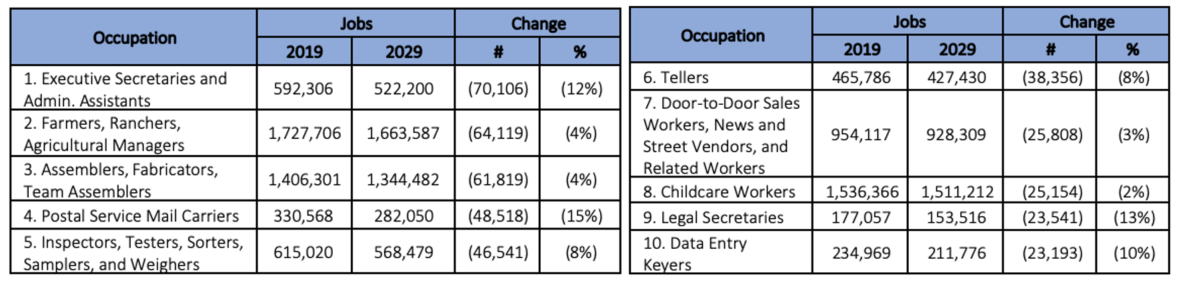

Table 2 shows the 10 occupations anticipated to be in greatest decline from 2019 to 2029 in the U.S. The occupation expected to see the largest decrease in number of jobs is executive secretaries and executive administrative assistants with a loss of 70,106 jobs, most likely as a result of automation, redefining of the occupation, and the growth and normalization of the teleworker. The table also shows other occupational categories being impacted through automation, such as bank tellers and data entry clerks. While the agricultural sector has been showing short-term occupational losses and is expected to see a decline, some predict that a shift to plant-based proteins and CBD to alter the forecasted trend.

Table 2: Top Declining Occupations in the U.S. (2019-2029)

The Changing Demographics of the Workforce will Force New Ways of Learning

The shift to a new economy brought on by the Fourth Industrial Revolution will have a direct impact on the demographics of the American workforce. Millennials will soon make up over a third of the U.S. labor force, which will make it the largest living generation in America in the workforce.ix They will continue to take over as managers and decision makers in the market, increasing their influence on the overall economy. The next generation (Generation Z or the iGeneration) includes those between the ages of 14 and 23 at the time of this publication and born between 1997 and 2006. These individuals are in high school, college, or are in this age group and chose not to go to college, as well as recent college graduates.[8] This cohort, along with young Millennials, makes up the new entry-level employee and adult learner and is often managed and influenced by their immediate supervisor, a Millennial in their thirties. Generation X will be the C-suite decision makers in the new economy as Baby Boomers phase out and move toward retirement. These younger adults not only have the numbers in the economy, but have also been gaining strength in the decision-making process and may reshape higher education moving forward.

The Supply of Online Degrees May Surpass Demand and Growth

With enrollments on the decline over the past eight years,[9] online degrees have served as a stopgap measure to an otherwise troubling financial situation for many colleges and universities. Online enrollments grew 5% in 2019 compared to 2018, with public institutions having 53% of the market, private nonprofit institutions 30% and for-profit institutions 17%.[10] While the number of online students continues to grow, the number of those with degrees entering the marketplace also appears to be growing. Pre-pandemic, many higher education experts believed that supply may have been outpacing demand, thus causing enrollments for established programs to be on the decline or not meeting anticipated goals for new students. Some had argued that given advancements in new learning and communications technology (e.g., videoconferencing, online collaboration and team tools, cloud management, and file sharing), coupled with recent global health scares, online enrollments could grow again in 2020 and 2021. The pandemic changed things significantly, causing the baseline for online education to rise significantly, as well as increasing the number of competitors exponentially in many cases. Online education was considered an advantage, but now has turned into a prerequisite for the delivery of higher education credentials.

Alternative Credentials as Means to Respond Quickly to the New Economy

To address the fast rate of change and needs of employers, institutions are expanding on a well-known concept that many longstanding continuing education units have historically offered, alternative credentials. Continuing education units have had a history of success offering noncredit programs, including certificates, customized training and intensive boot camps. With online degree growth being more competitive, the market and the new economy may be signaling for more modular learning, such as stackable or alternative credentials.

A 2017 Pearson and UPCEA survey showed that nearly three-quarters of institutions surveyed (73%) either strongly (40%) or somewhat (33%) agreed that their unit saw alternative credentialing as an important strategy for the future, up 9% from the previous year.[11] A 2020 UPCEA MindEdge survey showed that 70% of UPCEA members offer a form of alternative credentialing and another 26% plan to do so.[12] The advancement of alternative credentialing, whether created by higher education or business or industry, is inevitable as more Boomers leave economic leadership positions and Millennials assume the day-to-day decision-making roles. UPCEA has conducted a multigenerational manager survey[13] and found that as Millennials become managers, often in their thirties, they are more open to alternative credentials and other ways to learn. They also believe that the value of the degree has declined, as compared to other generations. The next generation, the iGeneration, comes into the workplace ready to learn online and in short bursts or modules. This generation also was the first to have curriculum developed for it in online or self-paced formats and as a result, is more prepared for learning in a manner where badges, certificates and other credentials are just-in-time, modular and stackable.

Summary

As the workforce evolves in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the demand for new workers, retraining or reskilling workers, and retaining workers is expected to accelerate. Institutions of higher education will need to not only prepare for the future worker and their degree needs, but also to educate a workforce without a degree and reskill those with a degree which has grown obsolete. There are also students in the higher education pipeline who are midstream or completing a degree that may not adequately prepare them for the direct needs of the new economy. One such case is the liberal arts or humanities degree holder or degree seeker. Recent research by Strada[14] and UPCEA[15] has shown that there appears to be a perception that liberal arts graduates are leaving college unprepared for tomorrow’s workforce. However, there is research suggesting that the competencies needed for the workplace, such as critical-thinking or effective communication, are skills employers are looking for. Furnishing these students with badges and stackable credentials which employers value as part of their curricular experience and providing them with supplemental instruction post-graduation in skills needed in the new economy are easy solutions for higher education.

As the 4IR continues to evolve, higher education must evolve with it. This new economy will create new jobs built off college and university degrees, as well as create new opportunities for workers migrating from old economy jobs in decline. These alternative credentials may be stackable and may have noncredit to credit pathways. The pandemic has created greater unemployment in the U.S., but also a change in perception toward higher education as many traditional colleges and universities shifted to online, which thus changed the value equation for a degree. With the economy quickly shifting, the approval process for new degrees is likely to be slow, thus opening the door for alternative credentials as an efficient pathway to careers in the new economy.

References

[1] Loss, Christopher P. Why the Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act Still Matters. (July 16 2012). From https://www.chronicle.com/article/Why-the-Morrill-Act-Still/132877

[2] Schwab, Klaus. The Fourth Industrial Revolution. (n.d.). From https://www.weforum.org/about/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-by-klaus-schwab

[3]Manyika, James, et al. Jobs lost, jobs gained: What the future of work will mean for jobs, skills, and wages. (November 2017) From https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/jobs-lost-jobs-gained-what-the-future-of-work-will-mean-for-jobs-skills-and-wages

[4]The Reskilling Revolution: Better Skills, Better Jobs, Better Education for a Billion People by 2030. (January 2020). From https://www.weforum.org/press/2020/01/the-reskilling-revolution-better-skills-better-jobs-better-education-for-a-billion-people-by-2030/

[5] Escobari, Marcela, et al. Realism about Reskilling – Upgrading the careers prospects of America’s low-wage workers. (December 2019). From https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Realism-About-Reskilling-Final-Report.pdf

[6] Jobs of Tomorrow – Mapping Opportunity in the New Economy. (January 2020). From http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Jobs_of_Tomorrow_2020.pdf

[7] Source: Economic Modeling Specialists International (EMSI) 2020.1 Dataset.

[8] Schneider, Joan, et al. How to Market to the iGeneration. Harvard Business Review. (May 6 2015).

[9] Fall 2019 Current Term Enrollment Estimates. (December 16 2019). From https://nscresearchcenter.org/current-term-enrollment-estimates-2019/

[10]New Data Confirms Growing Demand for Distance Education Programs. (February 27 2020). From https://www.nc-sara.org/sites/default/files/files/2020-02/NC-SARA_DataReport_PressRelease_27Feb20.pdf

ixGenerations-Demographic Trends in Population and Workforce: Quick Take. (November 7 2019). From https://www.catalyst.org/research/generations-demographic-trends-in-population-and-workforce/

[11] Fong, James and Janzow, Peter, et al. Demographic Shifts in Educational Demand and the Rise of Alternative Credentialing, Changes from 2016 to 2017. (December 2017). From https://upcea.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Demographic-Shifts-in-Educational-Demand-and-the-Rise-of-Alternative-Credentials.pdf

[12] UPCEA and MindEdge Inc. Survey on Alternative Credentialing. (March 2020).

[13] UPCEA. Millennial Manager Survey. (2018).

[14] Weise, Michelle et al. Robot Ready: Human + Skills for the Future of Work. (2018). From https://www.stradaeducation.org/report/robot-ready/

[15] UPCEA. Liberal Arts Recent Graduate Survey. (2018).

Jim Fong has more than twenty years working as a marketer and researcher in the higher education community. Prior to joining UPCEA’s Center for Research and Marketing Strategy, Jim worked as a higher education strategic marketing consultant and researcher for two firms and prior to that was the Director of Marketing, Research and Planning for Penn State Outreach. As a consultant, Jim worked with over a hundred different colleges and universities. While at Penn State, he was responsible for managing teams of marketing planners, competitive analysts, market researchers and enrollment management staff. Jim continues to teach graduate and undergraduate marketing and research classes for Drexel University, Penn State University, Duquesne University and Framingham State University.