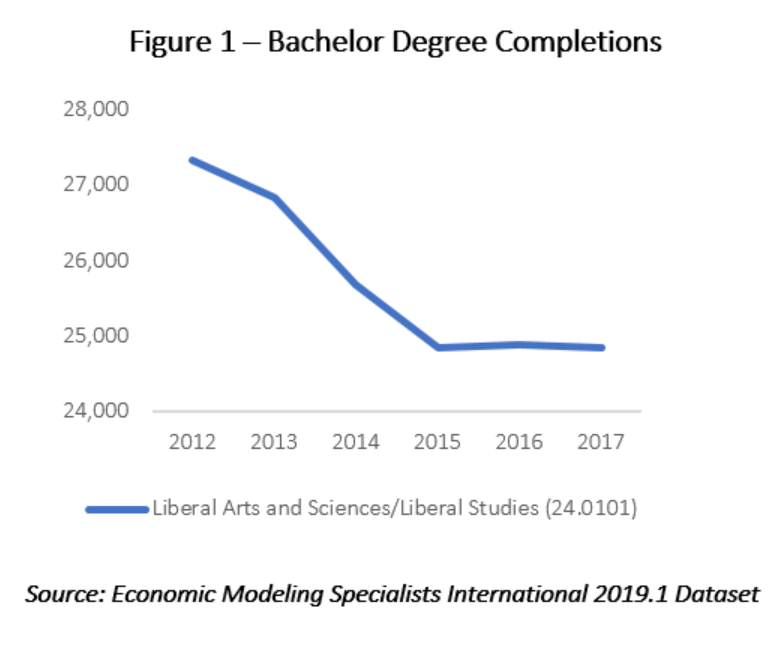

The economy is quickly changing, and the higher education community has responded by addressing curricula focused on career preparation in disciplines with the most pressing and obvious needs, technology and healthcare education. Institutions have created new degree and nondegree programs in data analytics, computer coding, and cybersecurity among others. With high job placement and above-average starting salaries in these sectors, many students are bypassing liberal arts degrees[1] in favor of career-oriented degrees and nondegree credentials that are often science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) related. As a result, student demand for liberal arts degrees has declined significantly over the past five years (Figure 1).

There appears to be a perception that liberal arts graduates are leaving college ill-prepared to contribute to the workforce compared with their counterparts graduating with STEM or business degrees. However, there is a body of research suggesting that the competencies underpinning a liberal arts education, such as critical thinking, communication, analysis, ethics, and problem solving, are precisely the types of skills employers are seeking in new hires.

UPCEA conducted research earlier this year to test these theories by measuring career success and jobs and educational satisfaction of recent liberal arts graduates compared to their counterparts who graduated with more technical and business-focused degrees. The study surveyed graduates about their post-college employment, asked them to reflect on their career preparation in college, and asked them to compare themselves to their counterparts who chose different academic pathways. Finally, UPCEA also conducted interviews with hiring managers and HR professionals to better understand their experiences with, and perceptions of, liberal arts graduates compared with their counterparts with other educational backgrounds.

Methodology and Respondents

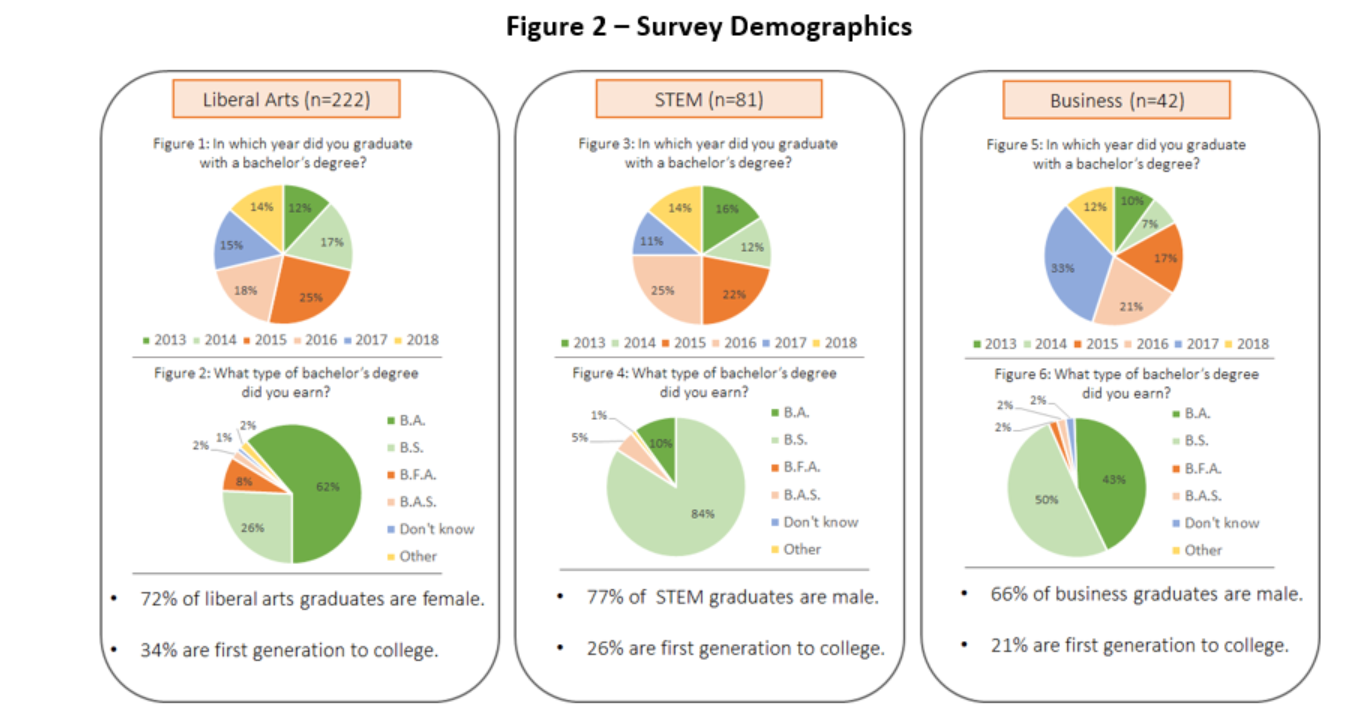

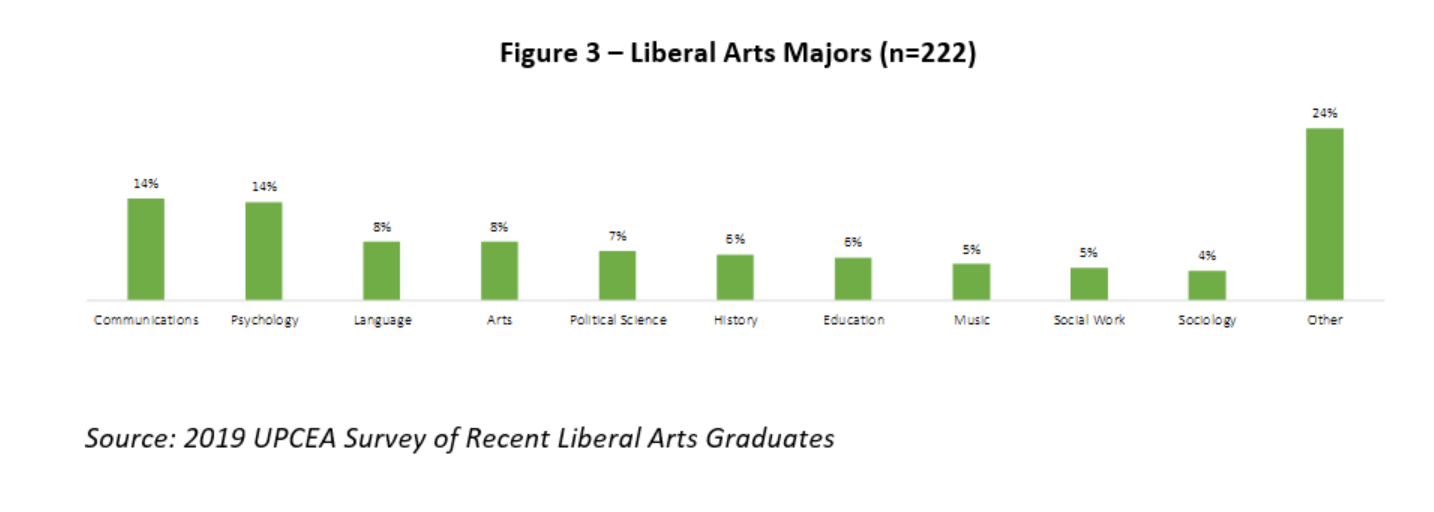

In early 2019, UPCEA’s Center for Research and Strategy surveyed 222 recent graduates (those earning their degree over the past six years) with a liberal arts degree and a comparison group of 123 that had either a STEM or business-related bachelor’s degree. In addition, the Center also interviewed a dozen employers to gain their perception of liberal arts graduates and gather ideas on how to increase the value of the degree. Both surveys were conducted on a national, random basis. Liberal arts graduates were initially surveyed and followed by the comparison sample a few days later. The proportion of liberal arts graduates to other graduates is not proportional to the general population. Figures 2 and 3 show some general demographics of the survey samples.

Key Findings

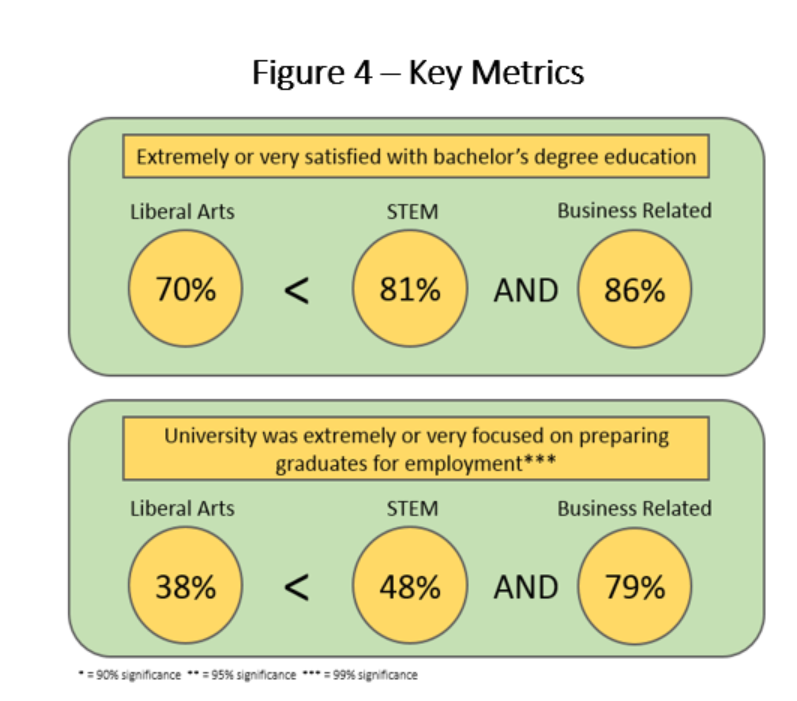

Figure 4 shows that liberal arts graduates are less satisfied (70% extremely or very satisfied) with their bachelor’s degree education compared to STEM (81%) and business (86%) graduates. Liberal arts graduates were also less likely to say that their institution was focused on preparing graduates for employment (38% said the institution was extremely or very focused) compared to STEM (48%) and business (79%) graduates.

|

Employment Search and Job Satisfaction

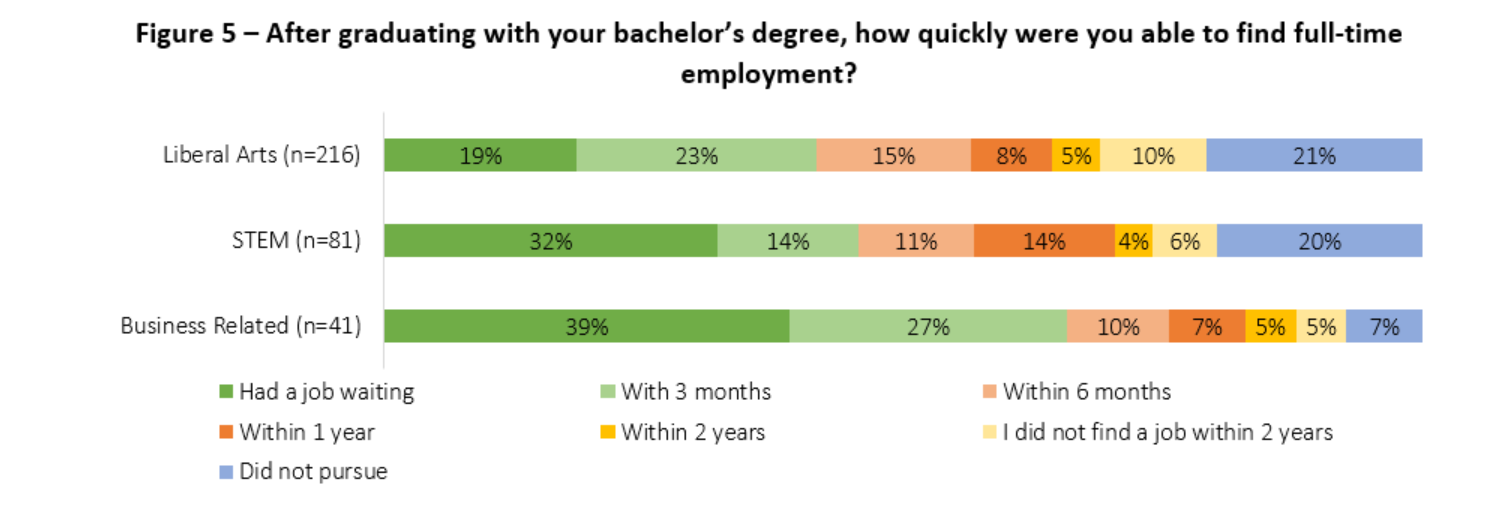

Figure 5 shows that liberal arts graduates were less likely to have a job waiting upon graduation (19%) compared to STEM (32%) and business (39%) graduates. However, respondents reported that within six months, 57% had found full-time employment, the same as STEM graduates. Seventy-six percent of business majors were employed full time within six months.

At the time of the research, 55% of liberal arts graduates were employed full-time and 20% part-time, lower than employment among STEM (73% full-time/9% part-time) or business graduates (81% and 12%).

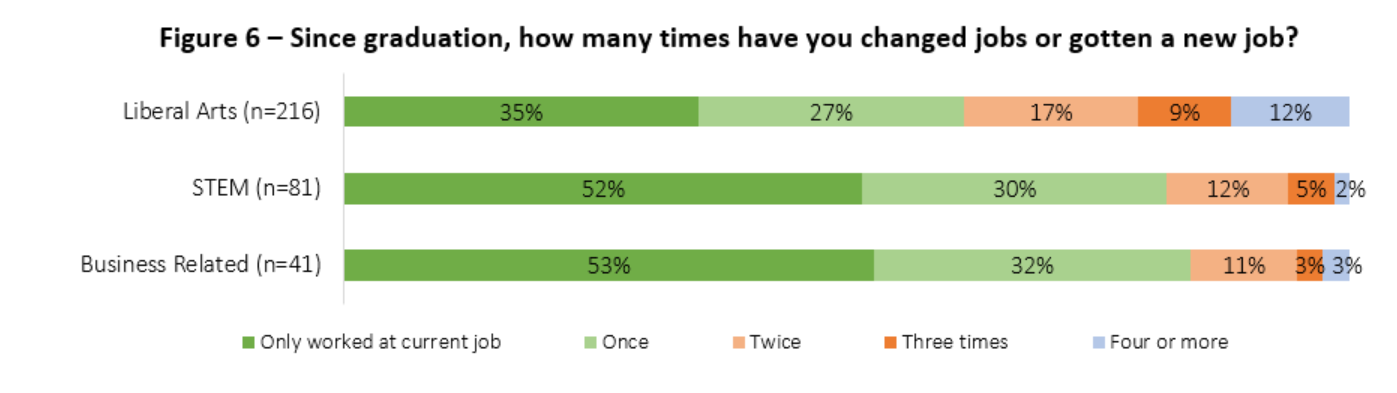

In addition to taking longer to find a job, participants with liberal arts degrees were more likely to have changed jobs multiple times since graduating. (Figure 6)

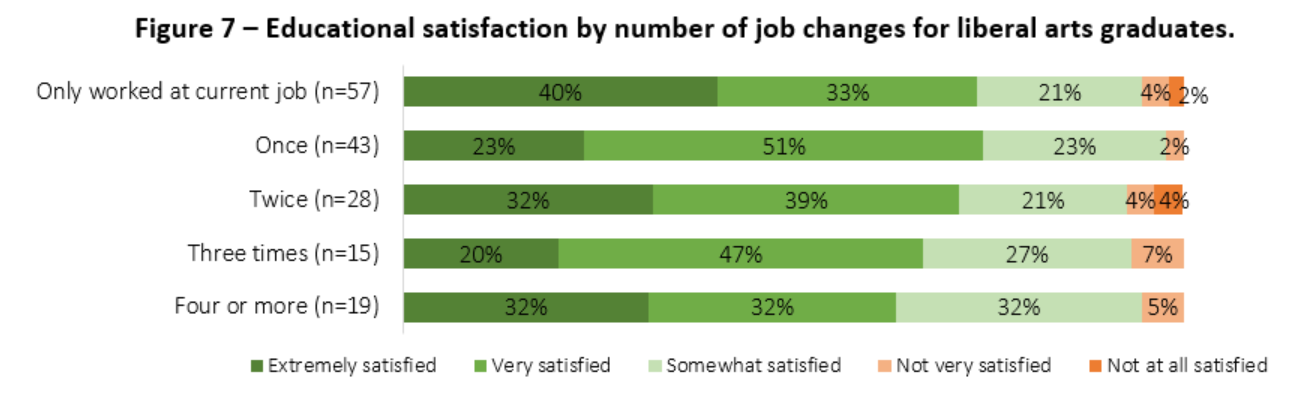

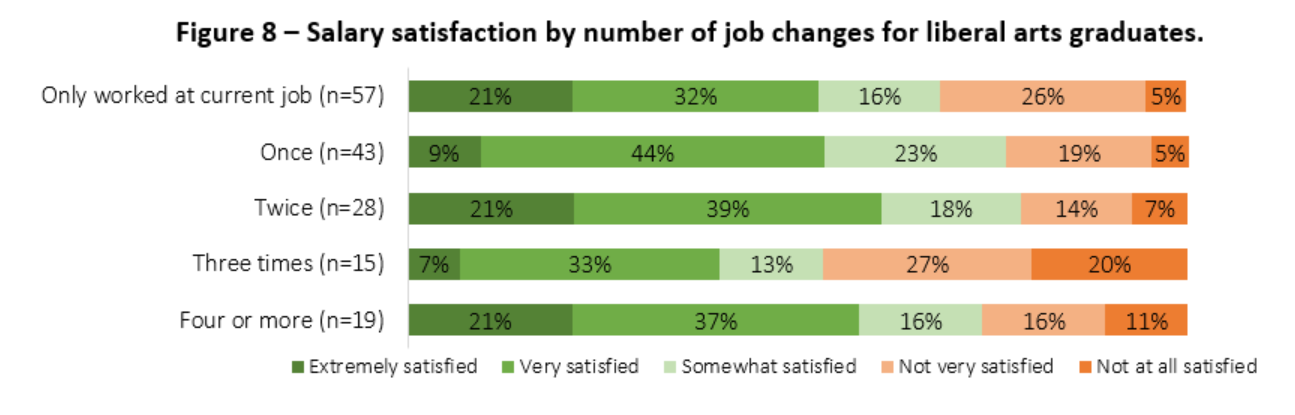

A recent study by Strada and Esmi[2] found that liberal arts graduates may not hit their stride until their second or third job, which may help explain the data in Figures 7 and 8. In each of these cases, liberal arts graduates who had changed jobs four or more times since graduation (in six years’ time, at the most) reported similar levels of educational and salary satisfaction (if not higher) as their counterparts with fewer job changes. These findings suggest that liberal arts graduates’ job changes may not be negative experiences, but rather may have been part of their search for a fulfilling career path.

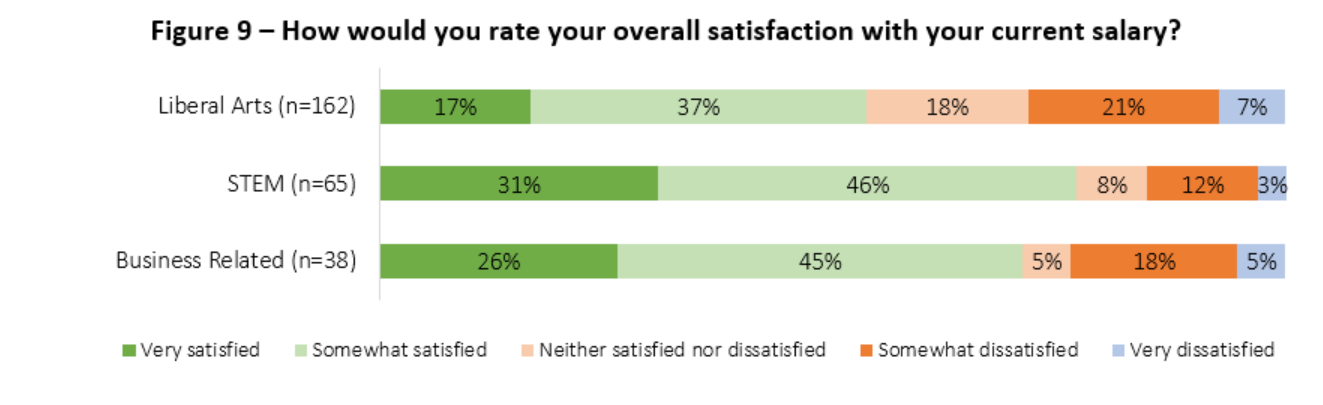

On the other hand, while more job changes may not negatively impact salary satisfaction among liberal arts graduates, they are overall less likely to be satisfied with their salaries (54% are extremely or very satisfied with their current salary) than STEM (77%) or business (71%) graduates. (Figure 9)

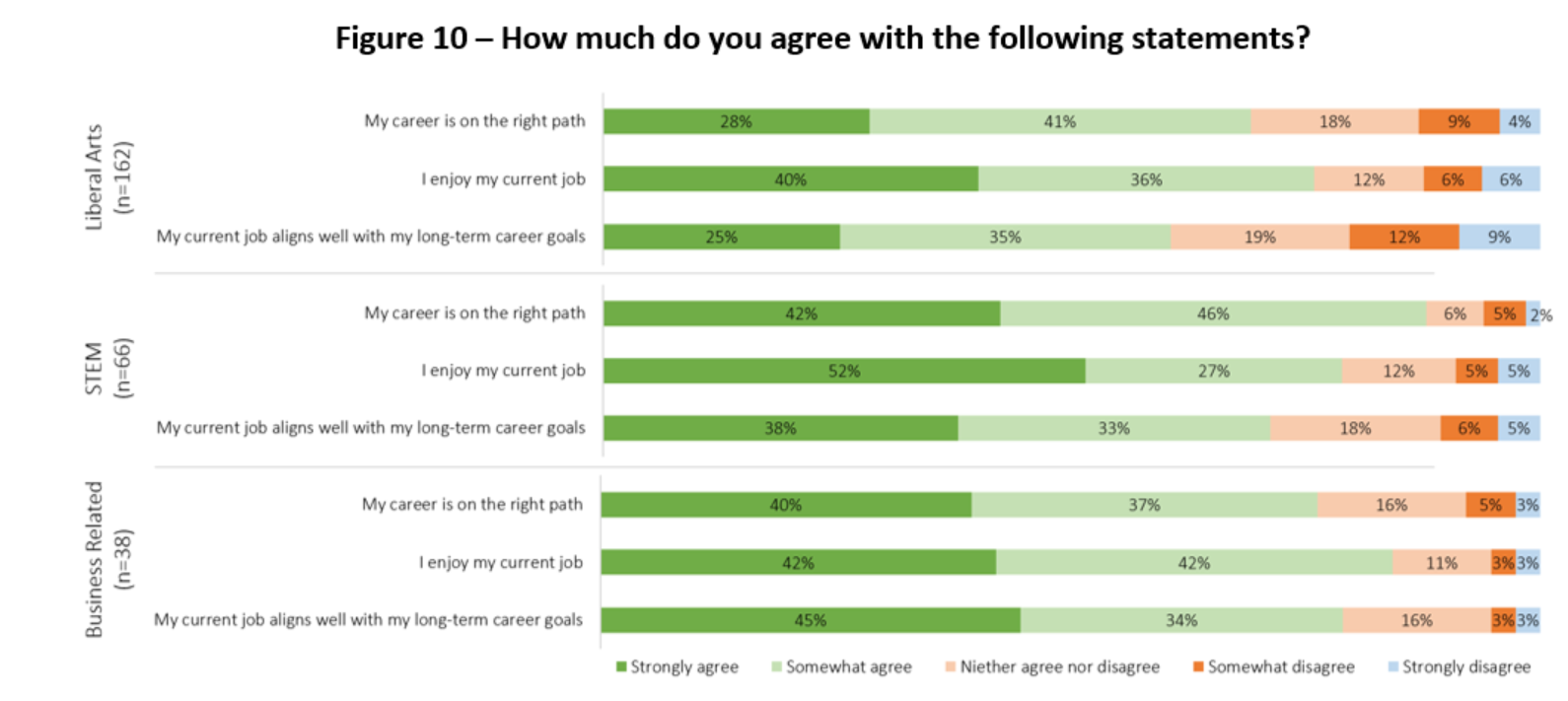

Similarly, liberal arts graduates are less likely than STEM and business graduates to enjoy their current job, believe it aligns with their long-term career goals, or feel that their career is on the right path. (Figure 10)

With liberal arts graduates reporting lower levels of employment and career satisfaction than their STEM and business major counterparts, the important question is: why? Is it indeed the case that liberal arts programs are not providing students with sufficient or appropriate preparation for future employment?

Employment and Career Preparedness

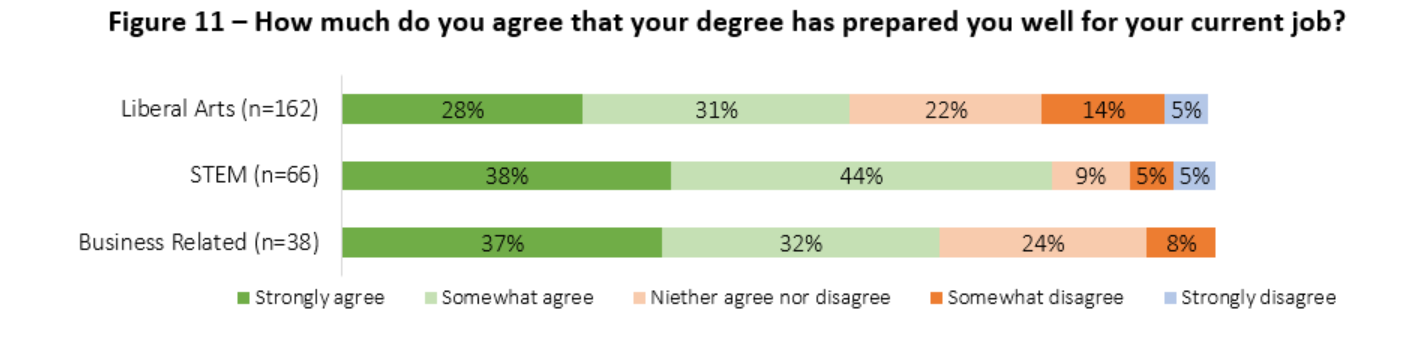

Survey participants were asked how well prepared they feel for their current job (Figure 11) and how prepared they are in comparison to their coworkers with different types of degrees (Figure 12). Just 28% of liberal arts graduates strongly agreed that they were well prepared, as compared to 38% of STEM and 37% of business graduates.

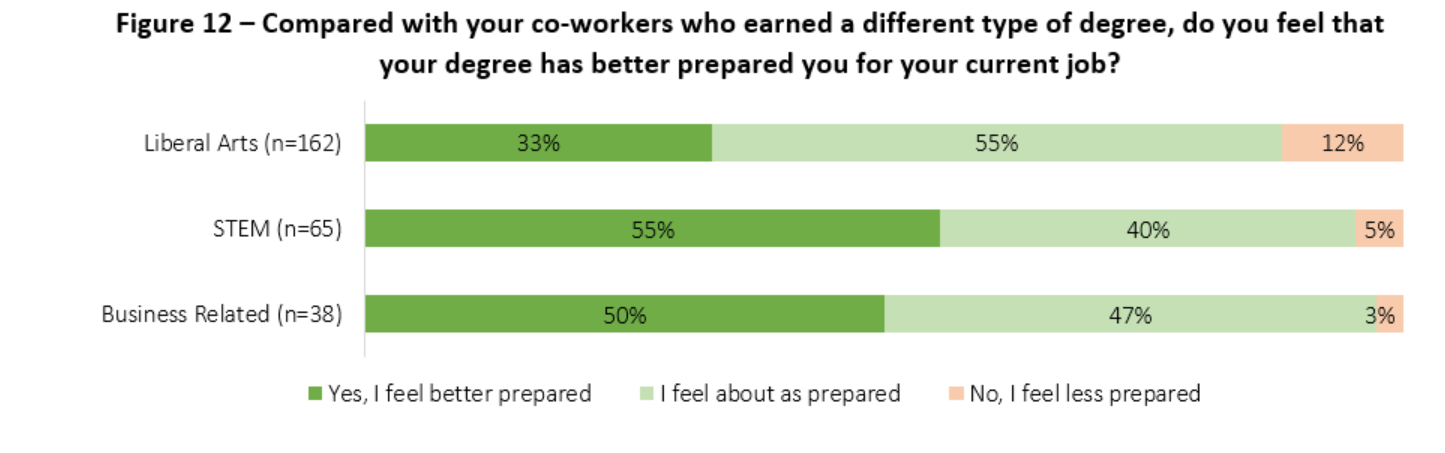

Only one-third of liberal arts majors consider themselves better prepared than their counterparts with different degrees, compared to 55% of STEM and 50% of business graduates. Although 12% feel less prepared, 55% think they are as well prepared as their counterparts. (Figure 12)

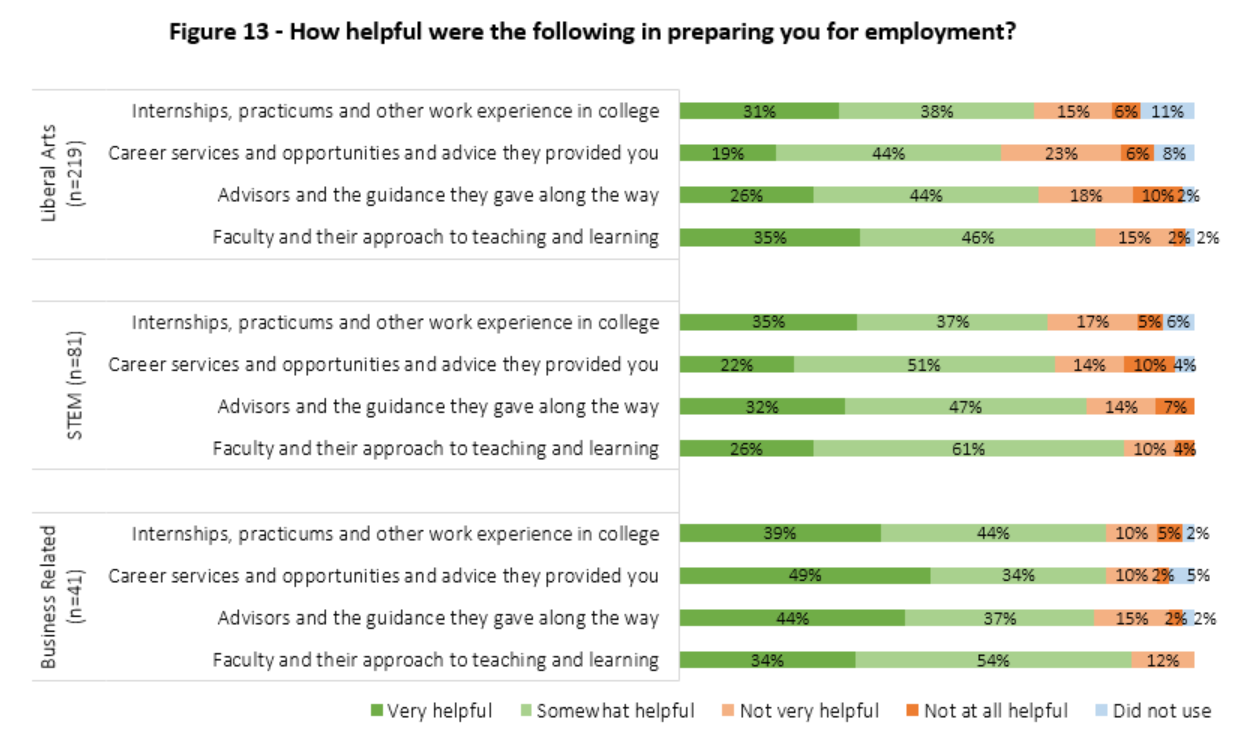

When asked about the various types of university career preparation resources they utilized in college, and how helpful each was for their future employment, liberal arts graduates were generally less likely to have found these resources helpful, particularly career services. Liberal arts graduates were more likely to report that faculty members and their teaching approaches were more helpful in employment preparation than other resources.

While fewer liberal arts graduates found university career resources helpful, more of them also reported that they did not use or participate in the listed resources. It is not clear, however, whether they elected not to use these resources, whether they were unaware of opportunities to participate because they had chosen a less career-oriented major, or whether the services were not available.

|

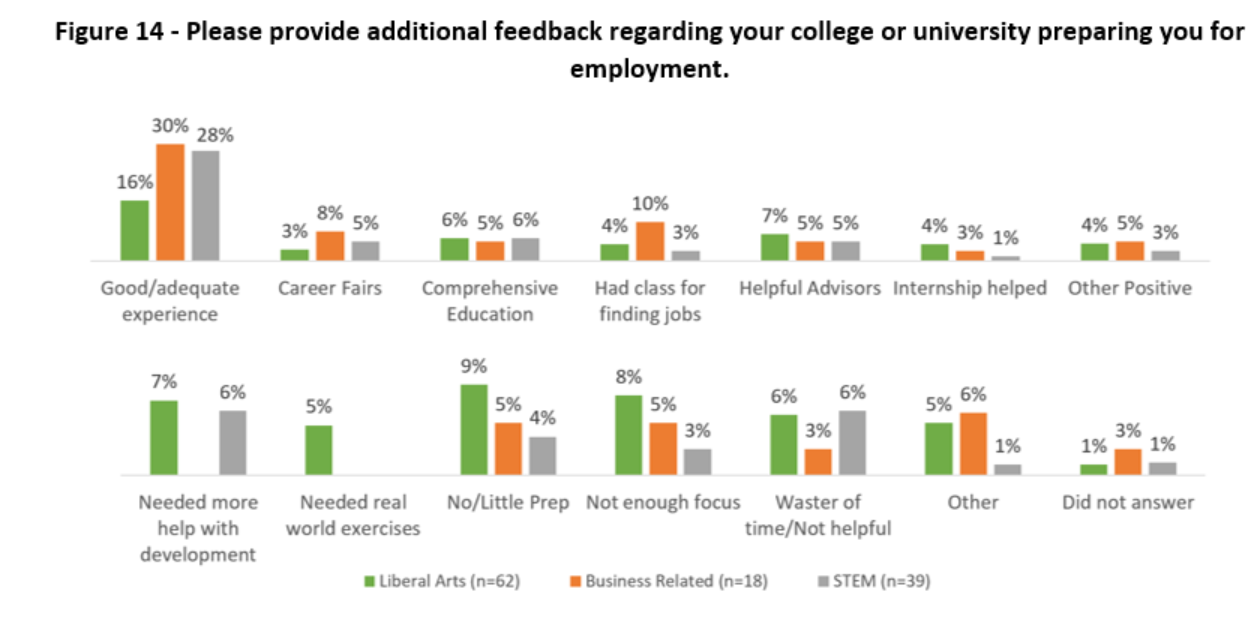

Liberal arts graduates were more likely to indicate that additional resources were needed and to speak negatively of existing resources, or the lack thereof, when asked to elaborate about campus job preparation resources. (Figure 14)

Liberal arts graduates’ lack of satisfaction with their current employment and their career trajectory compared to that of their counterparts with more career-focused degrees suggests there is a need to provide them with greater levels of career preparation support while they are still pursuing their studies. Raising awareness about campus career resources among students who have chosen a non-professional track, and encouraging them to take advantage of those resources, is likely a task to be shared by faculty members as well as staff.

Helping students understand the value of their studies as well as the skills and competencies gained during those studies and articulate this to future employers should be the responsibility of the entire student affairs and academic community surrounding liberal arts students.

|

Learning Outcomes and Competencies

It is generally argued that what new liberal arts graduates lack in applied knowledge and skills training, they make up for with well-developed “soft skills” competencies such as critical thinking, communication, analysis, ethics, and problem solving. Proponents of a liberal arts education suggest that these strengths help develop resilient, flexible, collaborative leaders who excel in the workforce and can quickly gain specialized knowledge on-the-job.

|

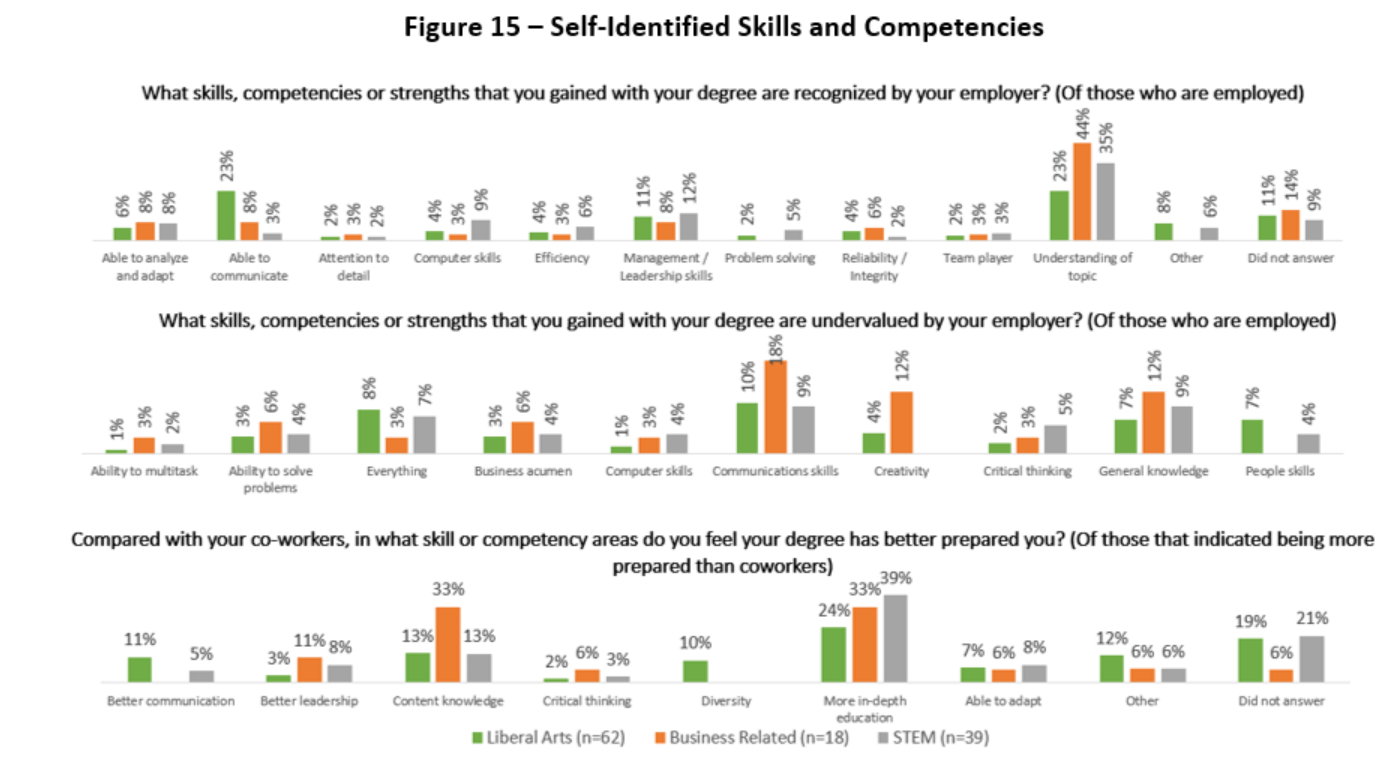

But does the reality live up to the expectations for liberal arts graduates? To understand the answer to this question, survey participants were asked to identify competencies, skills, and strengths they have gained with their degree studies, and indicate which of those strengths are recognized or undervalued by their employer, and which have helped them prepare better for their careers than their co-workers with different degrees.

Unsurprisingly, liberal arts graduates were most likely to indicate that their employer recognized their communication abilities (23%), compared to business-related (8%) and STEM graduates (3%). Leadership skills and topical understanding were other commonly noted, employer-recognized strengths by graduates in all three degree areas. Some liberal arts majors also indicated that their communications skills were undervalued by their employer (10%), though business graduates (18%) were particularly likely to feel this way.

When comparing themselves to co-workers, liberal arts graduates indicated that a more in-depth education (24%), content knowledge (13%), communication (11%), and diversity (10%) were competency areas that helped them better prepare for their job.

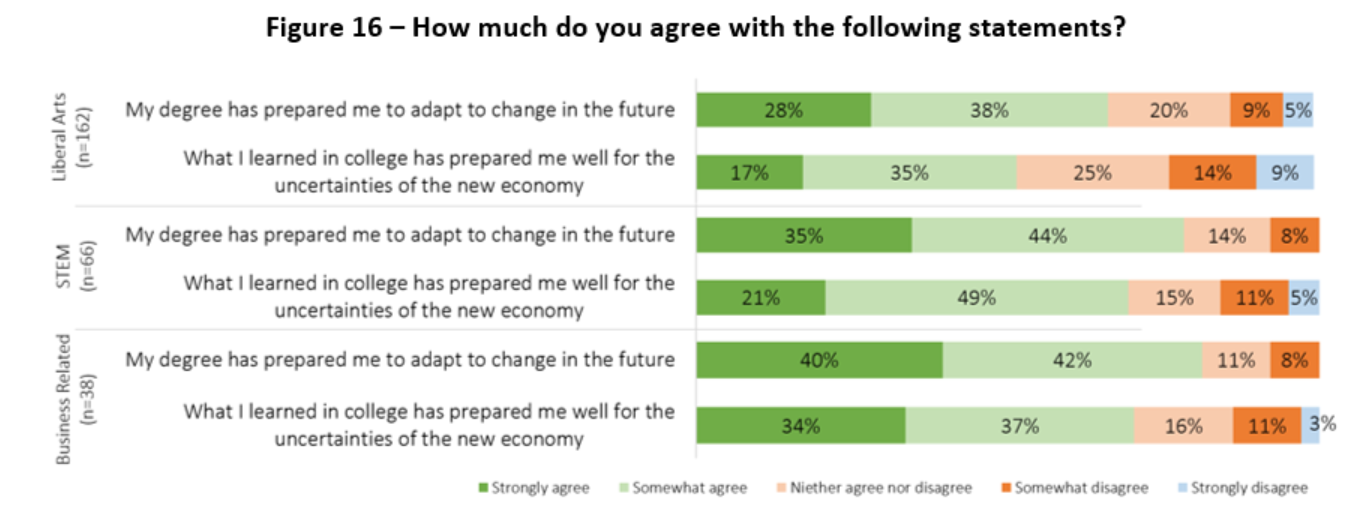

Often cited benefits of a liberal arts education are resiliency and adaptability born from strong problem solving and analytical competencies. However, survey respondents with liberal arts degrees were less likely than those with STEM and business degrees to agree that their degree had prepared them to adapt to change (66%) or to face the uncertainties of the new economy (52%).

It is unclear whether these relatively early career individuals are truly less prepared than their counterparts to address developments in the new economy and adapt to the way work will be conducted in the future, or whether they are not yet aware how to apply the competencies they have gained or how beneficial they will be. Regardless of which is the case, there is a need for liberal arts educators to address the gap.

|

Additional Credentials

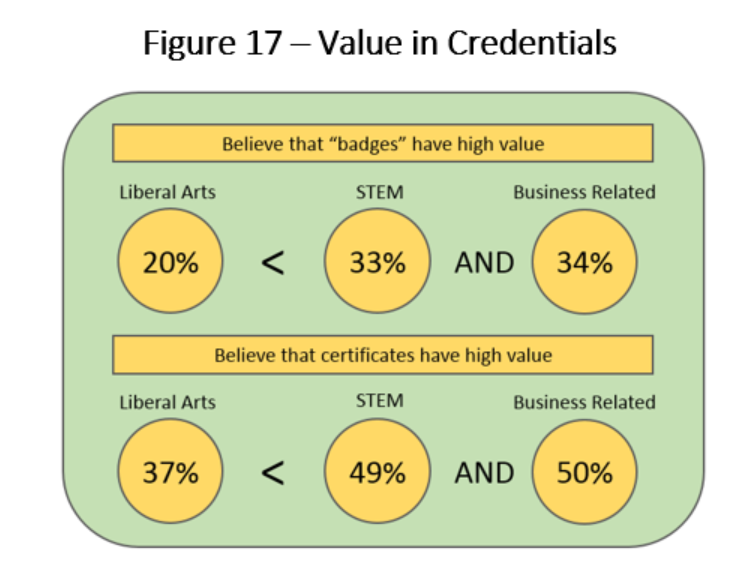

One of UPCEA’s hypotheses suggested that liberal arts graduates might place greater value on earning or having their skills recognized via a badge or certificate. However, this proved not to be the case, as 20% of liberal arts graduates placed a high value on a badge and 37% on a certificate. Approximately one-third of STEM and business graduates placed a high value on badge and one-half on certificates.

|

Employers, on the other hand, said they value certificates and badging as a method for cataloging or identifying competencies.

|

Employers also recognize their abilities, but often as a matter of on-the-job performance, as opposed to have clear evidence on one’s resume that they have a specific competency. Employers who were interviewed suggested that liberal arts graduates had good outward facing skills as well as critical thinking abilities. They also said that these individuals often brought with them more diverse experiences from other sectors.

Conclusions and Next Steps

Employers often state that they prefer to hire job candidates with business or STEM degrees, but when asked to list traits they are seeking in the employees, soft skills such as communication (both writing and speaking), problem solving, analytical skills, and teamwork, which are all features of a liberal arts education, are often mentioned as well. One of the employers interviewed for this research, Liz Kirschner, Head of Talent Acquisition at Morningstar Inc., noted that employers hire humanities and social-science graduates because “it’s easier to hire people who can write—and teach them how to read financial statements—rather than hire accountants in hopes of teaching them to be strong writers.” Similarly, The Wall Street Journal published an article in 2017 about liberal arts majors that quoted John Kroger, past president of Reed College, who said “College shouldn’t prepare for you for your first job, but for the rest of your life.” The article also stated that there is good news for liberal arts majors: “Your peers probably won’t outearn you forever.” In the long-term, once people reach their peak earnings years in their fifties, their earnings are about 3% higher than those with vocational degrees such as nursing and accounting. A recent article in The Chronicle of Higher Education also reported that liberal arts graduates close the pay gap over time, often matching the salaries of those who graduated in more career-focused disciplines.

Yes, with this current survey, just 33% of the liberal arts respondents feel they are better prepared in their current job than their STEM/business co-workers, but it may be in their next jobs, or the ones after that, that these numbers increase as they move into leadership roles as managers and executives.

As the urgency to address the issue of creating greater value from the liberal arts curriculum, the following should be considered or discussed further among the higher education community:

- Include more input from employers on curriculum planning

- Change the culture within the academic department or institution to focus more on employability and job readiness

- Consider the creation of alternative credentials to highlight the competencies of liberal arts graduates

- Create greater awareness of the strengths that liberal arts graduates have to the employer community

- Create more awareness of the value of badging and stackable credentials among future liberal arts students, as they believe that it has little value while employers place high value on it

- Improve how the competencies of liberal arts graduates can be better communicated on their resumes, LinkedIn profiles or in real-time in the workplace

- Partner with employers to facilitate communications about the competencies being instilled in liberal arts students and the value of new credentials as they are developed

As the economy forges ahead, with workplace shortages in areas well-suited for liberal arts graduates, higher education needs to take a more active and proactive role connecting these individuals in successful employment situations.

Jim Fong is UPCEA’s Chief Research Officer and the founding director of association’s Center for Research and Strategy. Prior to joining UPCEA, he served in a marketing leadership role for Penn State Outreach and the launch of their World Campus. He has taught a number graduate and undergraduate marketing, strategy and research courses at a number of colleges and universities, as well as designed a MOOC for the University of California, Davis. Jim regularly presents at UPCEA’s regional and national conferences, sharing vital information with attendees.

[1] The liberal arts are often defined as a combination of the humanities and social sciences, with humanities encapsulating courses or disciplines of history, writing, the arts and the classics, while social sciences include disciplines like political science, psychology, economics, etc. When referring to liberal arts in this white paper, the focus is on majors associated with these disciplines.

[2] The Real, Long-term Career Outcomes of Liberal Arts Grads, The Strada Institute for the Future of Work and EMSI, Weise, Hanson, Sentz, Saleh, 2018.